The Forgotten Art of Bookbinding and Its Modern Revival

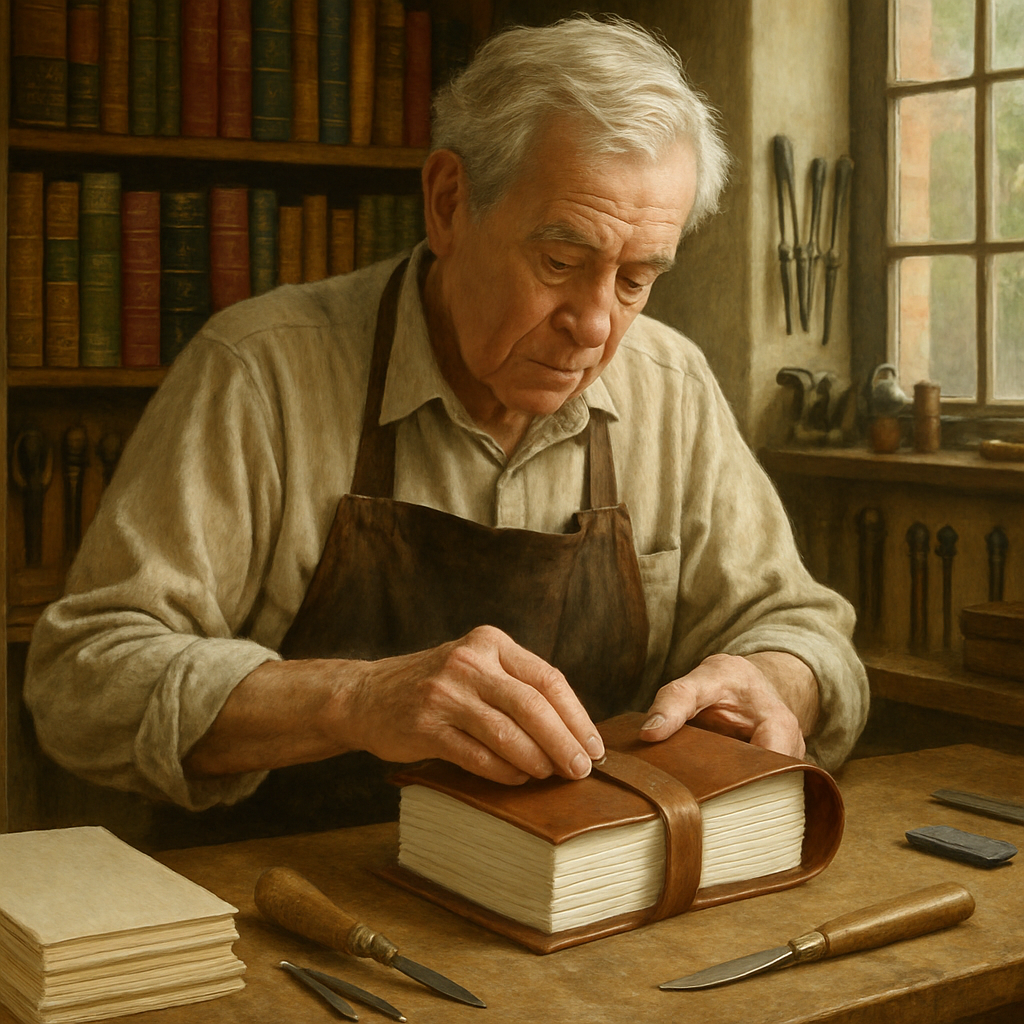

In the quiet corners of workshops across the world, a renaissance is taking place. Fingers press leather against board, needles thread through paper, and centuries-old techniques breathe new life into an art form that many thought technology had rendered obsolete. Bookbinding, once a necessary craft for the preservation and dissemination of knowledge, is finding its place in our digital world not as a relic, but as a vibrant, evolving art form that speaks to our deepest connections with the written word.

Long before the printing press revolutionized how we created books, each volume was a handcrafted treasure. Monks in medieval scriptoria would spend years copying texts, which would then be bound by skilled craftspeople using techniques passed down through generations. These weren’t just containers for information they were works of art, with tooled leather covers, gilded edges, and hand-sewn bindings that could last centuries.

The industrial revolution changed everything. Machine-made books became the norm, and traditional bookbinding retreated to specialty workshops and university conservation departments. By the late 20th century, with the rise of digital reading, physical books themselves seemed threatened with obsolescence. Why learn to bind books when fewer people were reading them at all?

Yet something unexpected happened. As our lives became increasingly digital, many people began to yearn for the tactile, the handmade, the unique. The same cultural shift that brought us artisanal coffee and handcrafted furniture has breathed new life into bookbinding.

The Ancient Craft in Modern Hands

Traditional bookbinding encompasses several distinct styles and techniques, each with its own history and aesthetic sensibilities. Coptic binding, developed in Egypt around the 2nd century AD, uses an exposed chain stitch that allows books to lie completely flat when opened. Japanese stab binding, with its distinctive patterns of thread visible on the spine, originated in China before spreading throughout East Asia. Western case binding, with its hidden stitching and hard covers, remains the standard format for most commercially produced hardcover books today.

“I started binding books because I couldn’t afford the rare books I wanted to collect,” says Maria Fredricks, a bookbinder from Portland who now teaches workshops across the Pacific Northwest. “Then I fell in love with the process itself. There’s something meditative about folding paper, measuring precisely, and seeing a book take shape under your hands.”

The basic tools of bookbinding haven’t changed much in centuries. Bone folders smooth tools traditionally made from animal bone are used to crease paper and work with adhesives. Awls punch holes for sewing. Needles and thread bind signatures (folded sections of paper) together. Presses hold books while glue dries.

What has changed is accessibility. Online tutorials, community workshops, and affordable starter kits have made entry into the craft possible for anyone with interest and patience. Social media platforms like Instagram and YouTube have created communities where binders share techniques and showcase their work.

Sam Johnson, who restores rare books at a university library in Chicago, notes that the revival has brought innovation along with tradition. “I’m seeing people combine traditional Western binding techniques with Japanese paper, or incorporating modern materials like Tyvek into otherwise classical structures. The rules are being rewritten.”

This blend of old and new reflects a craft in transition honoring its past while finding relevance in the present.

Why Make Books by Hand in a Digital Age?

The revival of handmade books raises an obvious question: why? In an age when most reading happens on screens and mass-produced books are more affordable and accessible than ever, what drives people to spend hours creating a single volume by hand?

For many, it’s about regaining control over an increasingly digital reading experience. E-books are convenient but ephemeral they exist as licensed content rather than owned objects. A handbound book is undeniably yours, from cover to text block.

“I bind my favorite poems and stories,” says Tanya Wu, a software engineer who took up bookbinding during the pandemic. “There’s something powerful about taking words that moved me and giving them a physical form that reflects how I value them. My copy of Neruda’s love sonnets isn’t just any copy it’s bound in red leather I cut and sewed myself.”

For others, the appeal lies in creating something that combines multiple art forms. Bookbinding incorporates elements of papermaking, printing, sewing, leatherwork, and design. The finished product can be as simple as a pamphlet stitched with linen thread or as elaborate as a full leather binding with gold tooling and marbled endpapers.

The slow, deliberate nature of the craft also appeals to many practitioners. In a world of instant gratification, bookbinding demands patience. A well-made book can’t be rushed. Each step folding, gathering, sewing, gluing, covering requires care and attention.

“I made plenty of mistakes when I started,” laughs Robert Chen, who binds limited editions of contemporary poetry from his apartment in Toronto. “I’d get impatient and try to move on before the glue was fully dry, or I’d measure carelessly and end up with crooked covers. You learn to slow down.”

This slowness extends to the experience of reading handbound books. Many binders report that books they’ve made themselves or that friends have made for them inspire a different kind of reading experience. The physical object demands attention in ways that mass-produced books or digital texts don’t always manage.

The environmental impact of bookbinding is complicated. On one hand, creating new books uses resources paper, board, cloth, leather, adhesives. On the other hand, the skills of bookbinding are essential for book repair and conservation, extending the life of existing volumes that might otherwise be discarded.

“I started binding because I wanted to fix my old paperbacks that were falling apart,” says Miguel Sanchez, who repairs books for a small library. “Now I teach basic repair techniques to library patrons. It’s amazing how many books get thrown away because of simple damage that could be fixed in minutes.”

The personal connection to handmade books extends beyond the maker. Handbound books make meaningful gifts, marking significant relationships or occasions. Wedding vows bound as a keepsake. A child’s first stories collected in a volume that can be passed down. A journal made specifically for a friend’s writing practice.

“I made a blank book for my dad when he retired,” says Chen. “He had always talked about writing his memoirs, so I bound a book with his initials tooled into the spine. Two years later, he handed it back to me, filled with stories about his childhood in Taiwan that I’d never heard before. That book is now one of my most valuable possessions.”

Learning the Craft

For those interested in exploring bookbinding, the path typically begins with simple structures. Single-section pamphlets require minimal tools and materials but teach fundamental skills like measuring, folding, and basic stitching. From there, many binders progress to multi-section books with more complex sewing patterns.

Local workshops offer hands-on guidance, while online courses provide flexibility. Books like Keith Smith’s series on binding techniques remain standard references, though newer titles often include more photographs and step-by-step instructions accessible to beginners.

The community aspect of learning shouldn’t be underestimated. Binding guilds exist in many cities, bringing together hobbyists and professionals to share knowledge and resources. Annual conferences feature demonstrations, exhibitions, and the chance to handle historical bindings that showcase the highest levels of the craft.

“I learned more in one weekend workshop than I did from months of trying to teach myself from books,” admits Wu. “There are so many little tricks that aren’t obvious until someone shows you how to hold the needle for the most efficient stitching motion, how to apply just the right amount of pressure when using a bone folder.”

The future of bookbinding seems secure, not despite digital reading but alongside it. As physical books become less necessary as information storage, they become more valuable as objects of art and connection. The handbound book speaks to something deeply human our desire to hold knowledge in our hands, to create lasting objects that outlive us, to engage with words through touch as well as sight.

In workshops and living rooms, on kitchen tables and in professional studios, the ancient craft continues to evolve. Each hand-sewn signature and carefully rounded spine represents not just a container for words, but a statement about what books mean to us beyond their content as physical artifacts of our relationship with reading, with craft, and with the tactile world that no screen can fully replace.